Week 14

Latino Immigrants in America

SOCI 231

Lecture I: December 2nd

Reminders and Updates

Response Memo Deadline?

Congratulations!

You do not have to submit another response memo this semester.

Reminders and Updates

Midterm Paper Grades

The grades for your midterm paper are available via Moodle.

You all did a great job.

Reminders and Updates

Final Paper

Final Paper Deadline

Your final papers are due by 8:00 PM on Wednesday, December 11th.

Reminders and Updates

Final Paper

More details will be provided on Wednesday.

Reminders and Updates

Latino Americans—

The Statistical Portrait

Largest Minoritized Subpopulation

Some Context from the Pew Research Center

The U.S. Hispanic population reached 62.1 million in 2020, accounting for 19% of all Americans and making it the nation’s second largest racial or ethnic group, behind White Americans and ahead of Black Americans, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. It is also one of the fastest growing groups in the U.S. Between 2010 and 2020, the country’s Hispanic population grew 23%, up from 50.5 million in 2010 (the Asian population grew faster over the same decade). Since 1970, when Hispanics made up 5% of the U.S. population and numbered 9.6 million, the Hispanic population has grown more than sixfold.

(Funk and Lopez 2022, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Largest Minoritized Subpopulation

Largest Minoritized Subpopulation

Largest Minoritized Subpopulation

More Context from the Pew Research Center

Largest Minoritized Subpopulation

Even More Context from the Pew Research Center

Largest Minoritized Subpopulation

Yes, Even More Context from the Pew Research Center

Largest Minoritized Subpopulation

The story of Latino American assimilation has

been heavily politicized and contested.

Largest Minoritized Subpopulation

A Question

Do you remember Zolberg and Woon’s (1999) key arguments?Largest Minoritized Subpopulation

Like their Asian counterparts, the Americanness of Latino-origin people—even those born in the U.S.—has been disputed.

Largest Minoritized Subpopulation

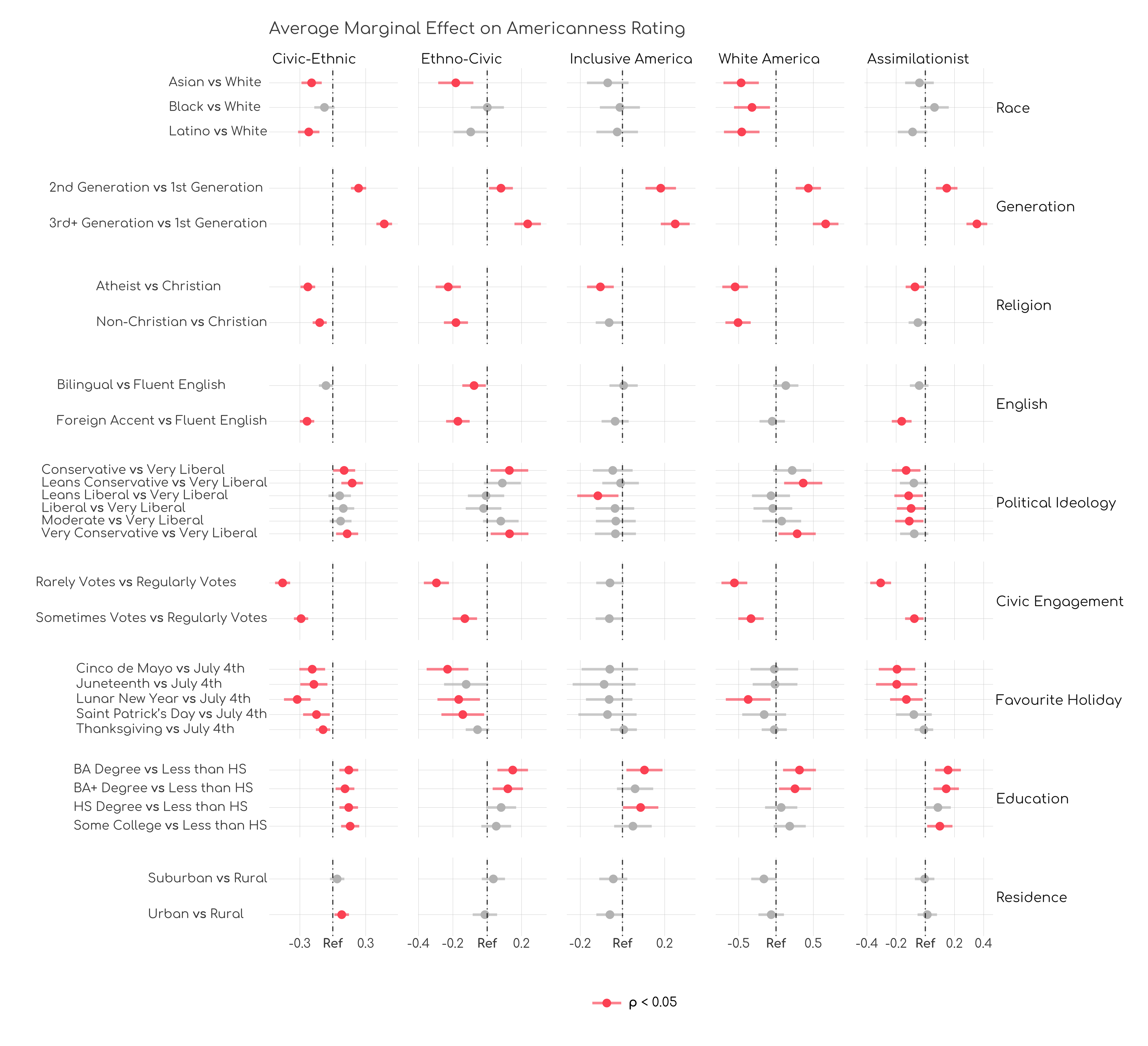

Preliminary Insights from Okura and Karim

Click Image to Expand

Becoming Latino(a) American —

Tanya Golash-Boza

Latinos and Americanness

At a rally in Siler City, North Carolina, one chilly afternoon in February 2000, David Duke told his attentive, although sparse, crowd that foreign elements wanted to take over his and their America … Duke did make himself clear that when he refers to America and American values, he is referring only to the direct descendants of European-Americans. By doing this, he elucidated what normally goes unspoken - that the unmarked label “American” in most cases means European-American.

(Golash-Boza 2006, 27, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Latinos and Americanness

“If the unhyphenated American label is reserved for white Americans … then to what extent can Latin American immigrants and their descendants become Americans?”

(Golash-Boza 2006, 27, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Latinos and Americanness

[P]art of being American is being able to ignore the prevalence of discrimination based on national origin in the United States. While whites self-identify as Americans, non-white Americans recognize that they are not Americans, but African-Americans, Native Americans, Asian Americans or Latino/a Americans. In this sense, how one becomes American or how one assimilates into American society depends in large part on one’s racial status.

(Golash-Boza 2006, 28, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Discrimination Against Latinos

Given the prevalence of prejudicial beliefs in the United States about Hispanics, one can surmise that people who are labeled as Hispanic are likely to experience discrimination at some time in their lives. However, within the segment of the U.S. population that the Office of Management and Budget defines as Hispanic, only some of the individuals actually have the physical and cultural features that result in their being considered Hispanic in daily interactions. Because not all Hispanics are easily categorized as Hispanic, Hispanics experience varying levels of discrimination … [T]hose Hispanics who do experience discrimination are less likely to self-identify as American because this discrimination increases their awareness of their non-white status in the United States.

(Golash-Boza 2006, 29, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Discrimination Against Latinos

Consequently, Golash-Boza (2006) posits that Latino Americans experience racialized assimilation into the putative mainstream.

Group Exercise I

Another Class Debate

Latin American Identities

Identification Patterns

Adaptation of Table 2 in Golash-Boza (2006)

Note: Data is from 2002 National Survey of Latinos.

Discrimination and National Identification

Adaptation of Table 7 in Golash-Boza (2006)

Note: 95% confidence intervals estimated based on table output (cf. Table 7 in Golash-Boza 2006). Ergo, they are likely a tad “off.”

Group Exercise II

Applying Concepts

Latinos and Racial Ambiguity

Latino Ambiguity

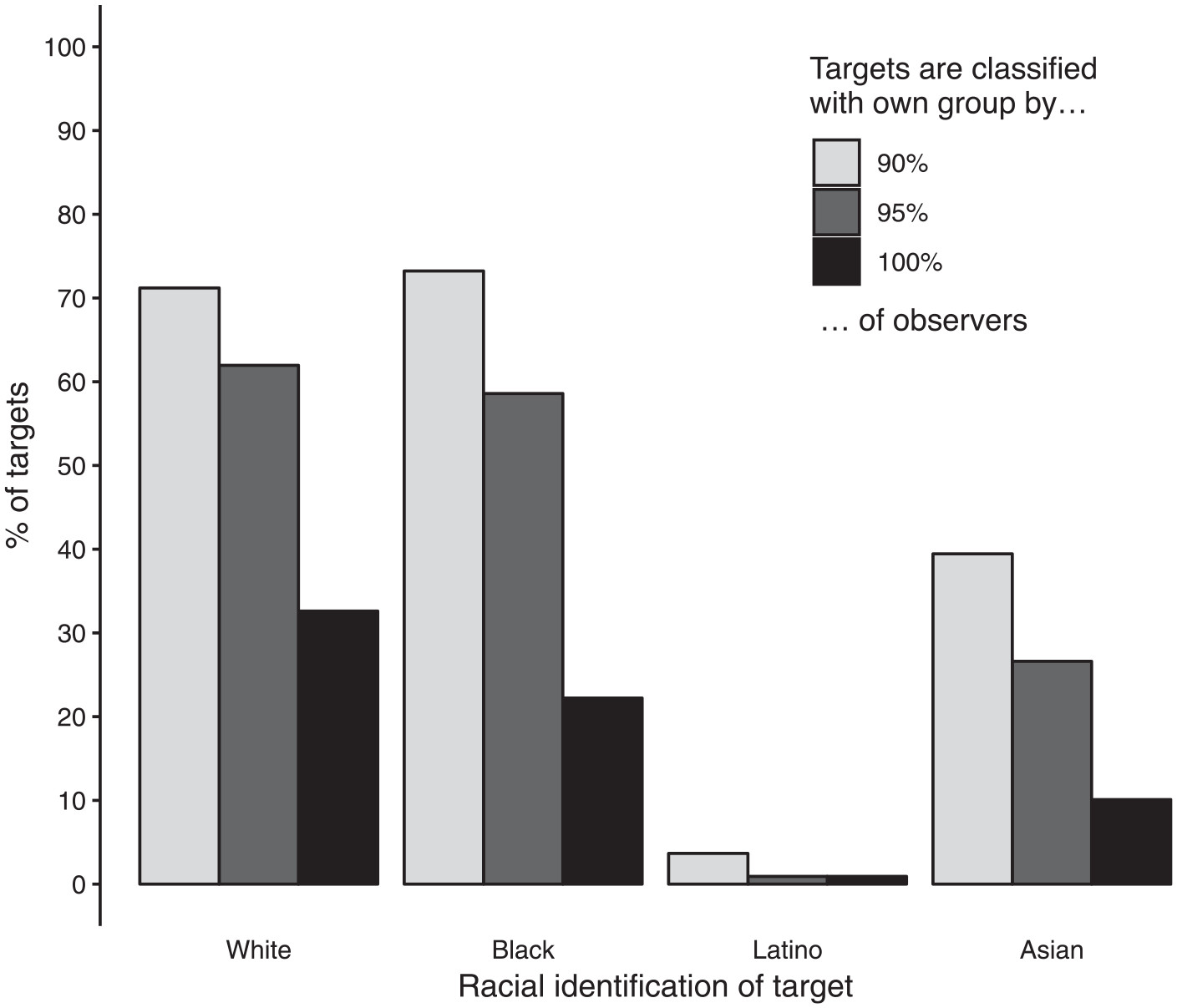

[S]elf-identified Latinos, who are themselves heterogeneous in terms of ancestry and phenotype, are probably the primary source of racial ambiguity in the United States today. A look at a racially diverse face database makes the point. The Chicago Face Database (CFD) … is a publicly available database of nearly 600 people who self-identify as White, Black, Latino, or Asian …[C]oncordance between self- and other-classification is lowest for self-identified Latinos. Concordance is highest for self-identified Whites and self-identified Blacks.

(Abascal 2020, 304, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Latino Ambiguity

Figure 1 from Abascal (2020).

Latino Ambiguity

As a result, Latino Americans will play a key role in the evolution

of ethnoracial boundaries in the United States.

Latino Ambiguity

White people who are prompted to think about the changing demographics of the United States are less likely to classify people who are ambiguously White or Latino as “White.” This suggests White people respond to demographic threat by contracting the boundary around Whiteness.

(Abascal 2020, 302, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Latino Ambiguity

What does this mean, exactly?

Latino Ambiguity

Studies consistently find that White people are more likely to marry and live near Latinos than Blacks … [T]hese facts are taken to mean that “racial boundaries are more prominent, and the black/white divide more salient than the Asian/white or Latino/white divides” (Lee and Bean 2004, 229). However, social scientists have also observed that both intermarriage and integration are lower in areas where immigration is higher … Explanations for this association typically stress structural features of communities rather than individual preferences … (My) findings suggest preferences may also play a role: White people in high-immigration areas might be less likely to count Latinos as candidates for inclusion in White social spaces. In short, where Latinos are more concentrated, the White/Latino boundary is brighter and the benchmark for being considered “honorary Whites” higher.

Latino Ambiguity

More fundamentally, (my) findings imply that White people will increasingly fortify the boundary separating Whites from non-Whites as the Latino and Asian populations continue to grow and the U.S. population diversifies.

(Abascal 2020, 316, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Exercise III

Ambiguity and Assimilation

Group 1

Use neo-assimilationism to theorize how ethnoracial ambiguity is related to the assimilation of Latinos in the United States.

Group 2

Use the segmented assimilation perspective to theorize how ethnoracial ambiguity is related to the assimilation of Latinos in the United States.

Lecture II: December 4th

Reminders and Updates

Response Memos

Grades for your nine response memo submissions

are available via Moodle.

Reminders and Updates

Participation

Grades for class participation will be posted next week.

Reminders and Updates

Final Paper

Final Paper Deadline

Your final papers are due by 8:00 PM on Wednesday, December 18th.

Still, you should try to submit the term paper

sooner rather than later.

Reminders and Updates

Final Paper

Guidelines for the term paper can be found here.

Reminders and Updates

A Question

Who is unavailable next Wednesday from 2:00 to 3:20 PM?Reminders and Updates

Who Identifies as “Latinx”?—

G. Cristina Mora, Reuben Perez and Nicholas Vargas

The Power of Labels

Ethnoracial labels, like other terms used to refer to categorical communities, are not benign; rather, they are imbued with symbolic power … and communicate moral, social, and even historical understandings of group boundaries and social positioning … Terms like “Oriental,” “Mulatto,” and “Spanish Origin” are all examples of how communities are officially labeled in ways that can bound and classify them, and thus communicate strong messages about the groups’ social standing and even moral valuation … And while individuals might use terms like “Hispanic” or “Indian,” for example, regularly without necessarily thinking about the political origins of those labels, this casual usage does not deny the power dynamics and processes that came into play to generate the labels in the first place.

(Mora, Perez, and Vargas 2022, 1172–73, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Power of Labels

Likely because of the importance of power in label construction, the politics of ethnoracial labels has long been approached through the lens of the state or of ethnic elites … (Thus,) hardly anything is known about how non-elites and target populations understand and come to adopt new labels—especially during their initial stage of development. Indeed, most work on ethnoracial labels acknowledges that survey or empirical examinations of label adoption do not emerge until decades after the terms have been formally institutionalized … And in those cases where labels became only partially institutionalized, we have almost no public survey data and very little empirical research on who was amenable to using those labels.

(Mora, Perez, and Vargas 2022, 1172–73, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Power of Labels

A Question

Why is this consequential?The Power of Labels

Patterns of self-categorization offer an “opportunity to understand how intersectional politics, especially concerning race and gender, impact the way that communities define themselves”

(Mora, Perez, and Vargas 2022, 1171, EMPHASIS ADDED).

The Power of Labels

Mora and colleagues (2022) identify two key variables that should

powerfully pattern the “early adoption” of labels like Latinx.

Generational Status

Partisan Identity

Panethnic Labels Among Latinos in America

Identificational Patterns

The first survey to ask non-elites, or the general Latino community, about their label preferences was the Latino National Political Survey (LNPS) …The survey was fielded in 1989-1990, nearly 20 years after the term “Hispanic” was adopted by political movements and media organizations and a decade after it was officially institutionalized in the US Census Bureau forms. Still, analysis of this early data reveals important trends that can shed light on the “Latinx” issue. The data show, for example, that in the late 1980s second-generation immigrants were more likely than first- or third-generation immigrants to adopt a panethnic label (“Hispanic” or “Latino”), and that those that were more politically progressive were also more likely to identify panethnically than their more conservative counterparts.

(Mora, Perez, and Vargas 2022, 1175, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Identificational Patterns

This early literature often positioned panethnic

labels as mutally-exclusive.

Identificational Patterns

Identificational Patterns

Given that, we might assume that the adoption of a new panethnic label might not mean a simple substitution of “Latinx” for “Hispanic” or “Latino,” for example. Rather, it may mean that individuals develop a collection of labels inasmuch as they might sometimes identify as “Latinx,” but at other times still use the “Latino” and “Hispanic” identifiers.

(Mora, Perez, and Vargas 2022, 1176, EMPHASIS ADDED)

The Latinx Case

A Site of Contestation

As (Latinx) became more popular in US publications, it began to generate considerable and passionate debate, especially on college campuses. In a 2015 Swarthmore College news article, professors Guerra and Obrea admonished those that used the term, calling it a mere “buzzword” and arguing that “by replacing o’s and a’s with x’s [Latinx] is rendered laughably incomprehensible to any Spanish speaker without some fluency in English” … They further contended that using “x” as a seemingly gender-neutral alternative is a form of “linguistic imperialism—the forcing of U.S. ideals upon a language in a way that does not grammatically correspond with it” (Guerra and Orbea 2015).

(Mora, Perez, and Vargas 2022, 1176–77, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Discussion I

Critics and Proponents

In groups of 2-3, discuss other arguments for and against the institutionalization of the Latinx label that were

summarized by Mora et al. (2022).

Findings From California

So, Who Identifies as Latinx?

Adaptation of Figure 1 in Mora et al. (2022)

Note: Descriptive findings from January 2020 California Poll.

So, Who Identifies as Latinx?

Adaptation of Table 2 in Mora et al. (2022)

Note: 95% confidence intervals estimated based on rounded table output (cf. Table 2 in Mora et al. 2022). Thus, they are likely a tad “off.”

Political Backlash

The Politics of Identity

The Latinx label may be shaping institutional politics in America

(cf. d’Urso and Roman 2024).

The Politics of Identity

The Politics of Identity

[W]e … provide observational evidence that 1) Latinos are less likely to support a politician who uses the phrase “Latinx,” a gender-inclusive group label, in their appeals to the Hispanic/Latino community; 2) Latinos who oppose the phrase “Latinx” to describe the broader Latino/Hispanic community are less likely to support Democratic politicians who have used or are associated with “Latinx.” Moreover, we demonstrate these statistical patterns are driven by Republican, conservative and anti-LGBTQ+ Latinos that we may expect to be predisposed against the inclusion of queer and gender minority Latinxs.

(d’Urso and Roman 2024, 1–2, EMPHASIS ADDED)

Group Discussion II

Interpreting the Findings

Group Exercise I

Cultural Taste and Assimilation

Enjoy the Weekend

References

Note: Scroll to access the entire bibliography